At the Crossroads of Fundamentalism and Humanism:

Recalling Bernie Sanders's Visit to Liberty University

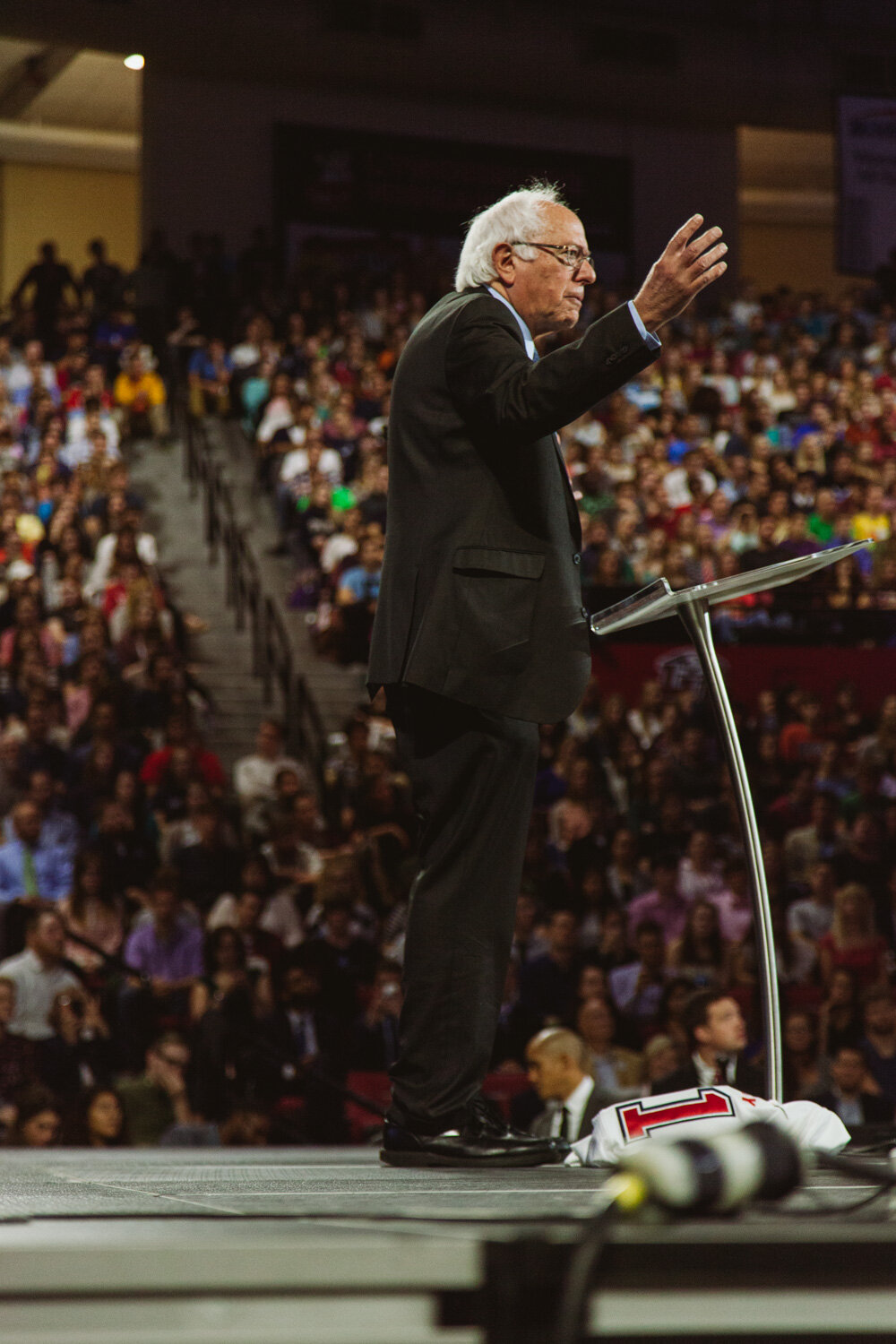

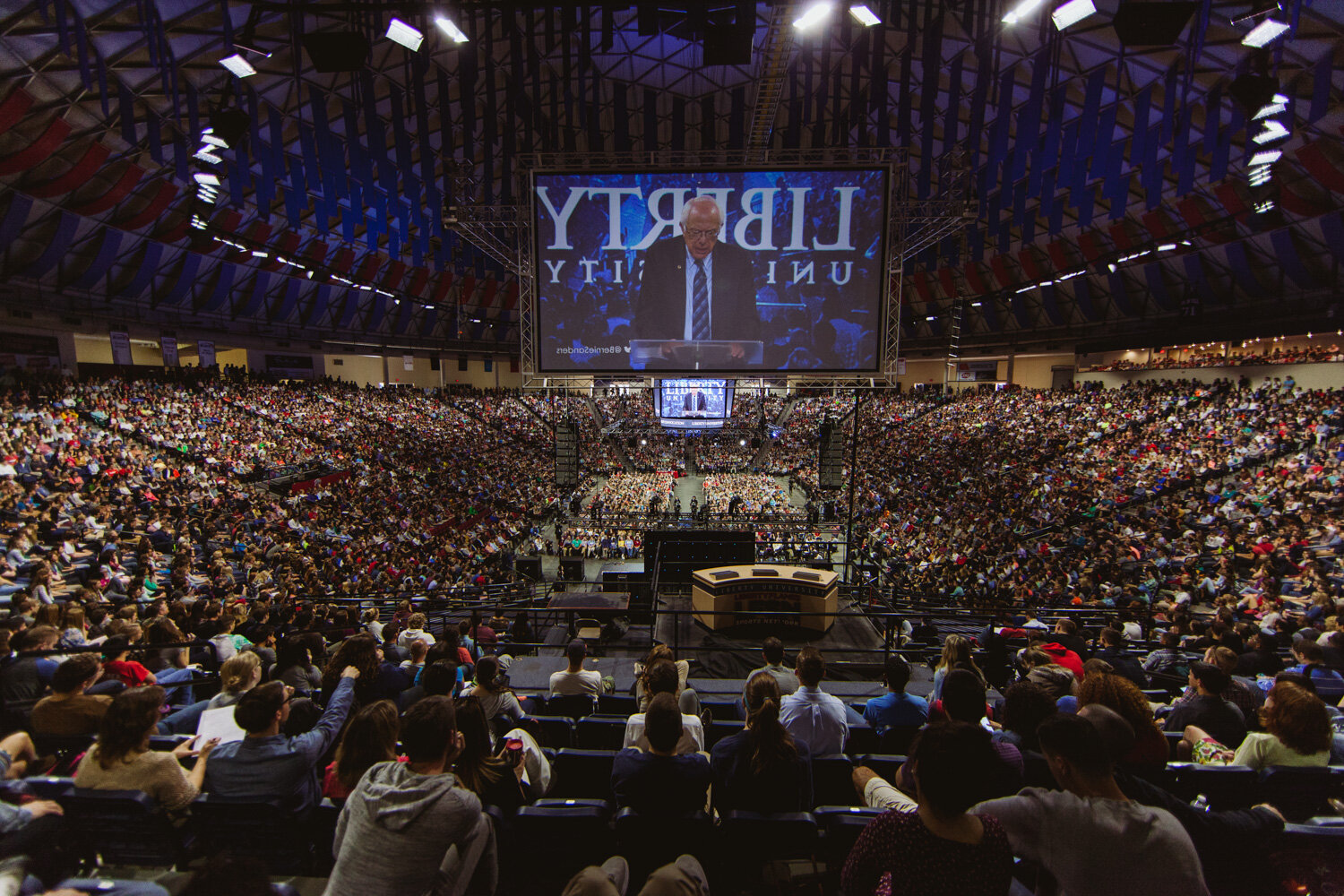

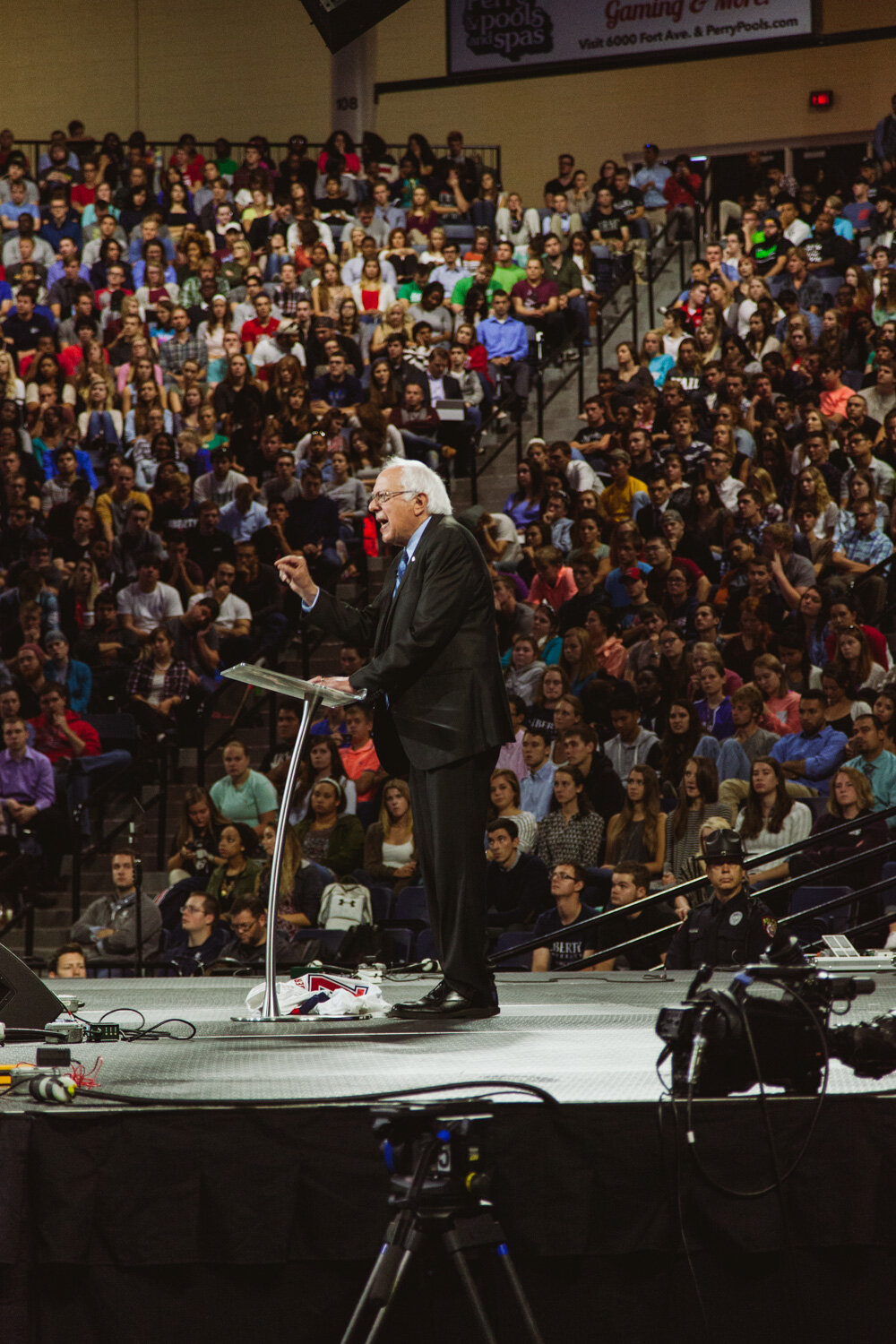

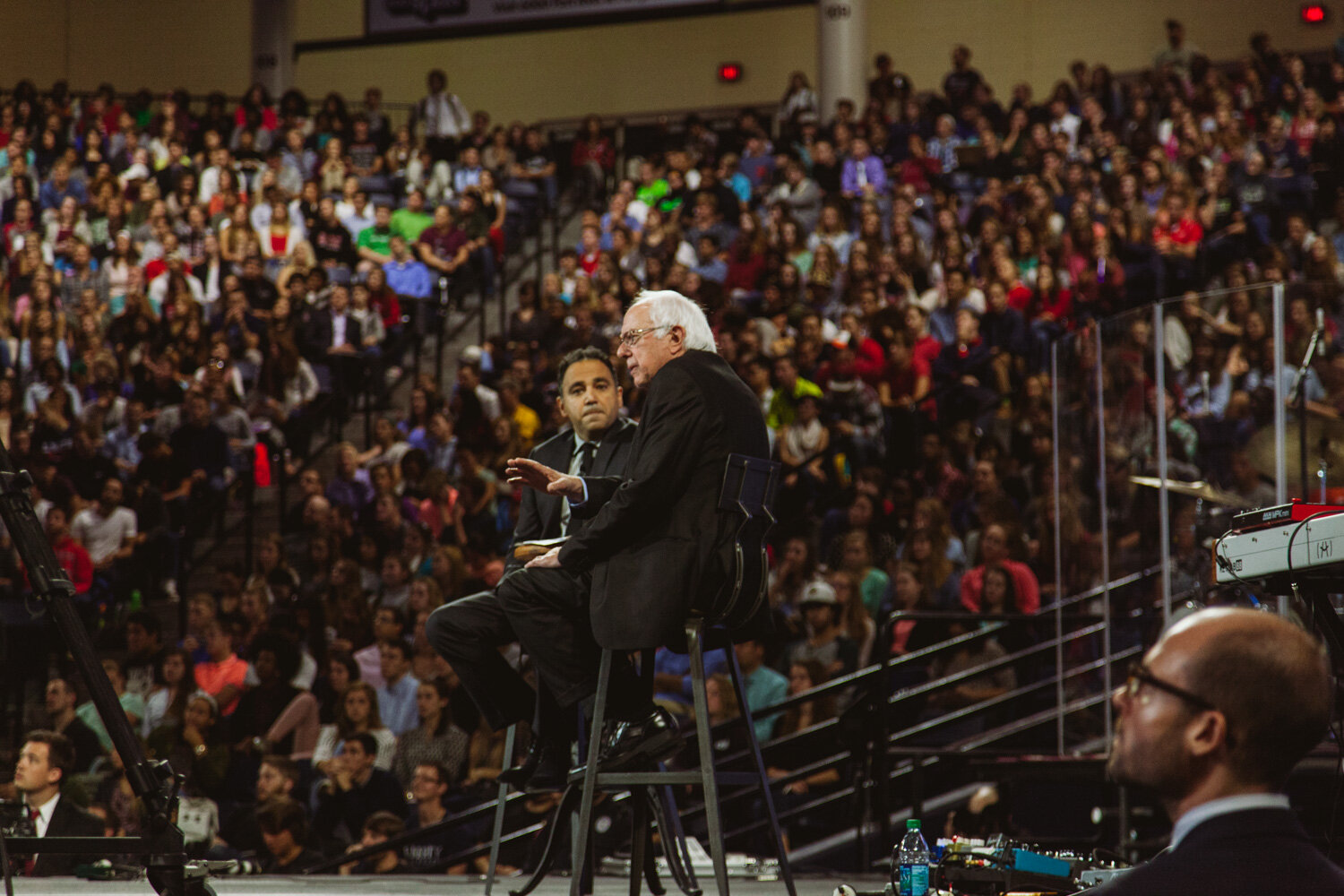

Liberty University students, among others, enter The Vines Center in Lynchburg, Virginia, on September 14, 2015 to hear US Senator Bernie Sanders speak.

“It may be that the human race is not ready for freedom.

The air of Liberty may be too rarefied for us to breathe.”Steven Pressfield, The War of Art

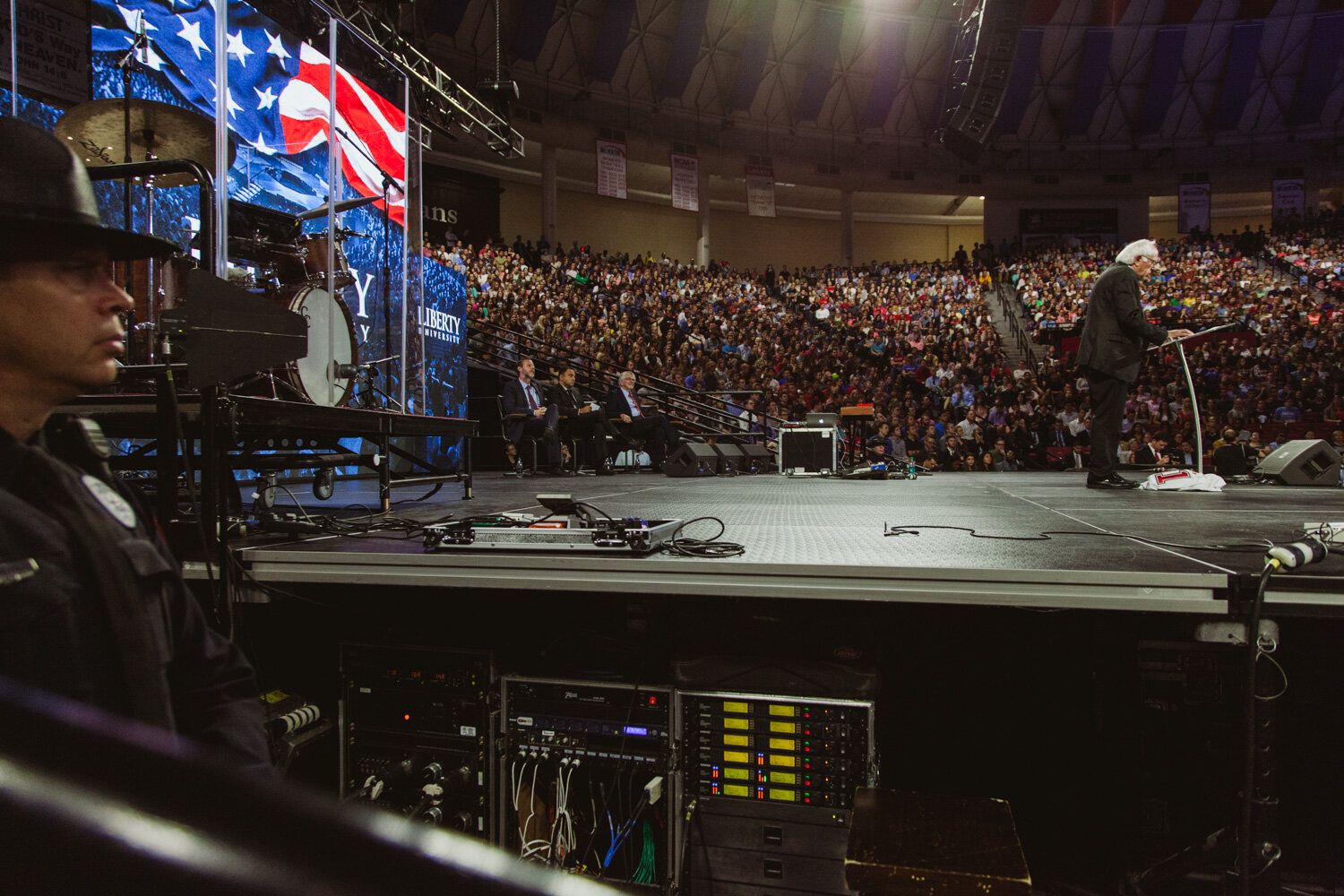

A news reporter gets ready to speak into the camera with the swelling in the background.

The scene at Liberty University on September 14, 2015, was a familiar one, as was the creeping feeling of overwhelming inauthenticity, likely stemming from the fact that 10 years ago I sat in those same seats three times per week attending what the university ardently claims is not a worship service, listening to people preach and sing about God. Every so often a political speaker would come through, but one could (so to speak) lower the volume on what was being said and not miss a thing. It was always the same.

That same feeling persisted while I worked as a copywriter and editor for the school’s propaganda department in 2010. It only alleviated itself once I finally left the position (and my seat in my graduate English classes 18 months later), and stepped away from 25 years of living within the Evangelical Christian community.

On this particular morning, I let the feeling pass over me while Liberty University Senior Vice President for Spiritual Development David Nasser prayed into the microphone, to be heard by millions:

“I pray that today, Father, that you would teach us, God, that you would use our guest today to help us know not just what to think but how to think.”

Before the guest, Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, could rise to the podium, Nasser delivered an enthusiastic update on how a student in financial need was given $7,000 in excess of what was required for her to stay in school. She in turn decided to give the surplus to other students in need.

Another report: Students, thousands more than were expected, showed interest in a new outreach campaign to the point that the website kept crashing.

“It is by far the largest single response we’ve had like that as a student body,” Nasser said, “and I think it just goes to show that nobody is a greater servant than a Liberty University student.” It was the first of two wildly hyperbolic sentiments Nasser would utter — well aligned with my overall LU experience.

As if to serve as a reminder to those in attendance and viewing around the world of the particular socio-intellectual climate they were entering into, the praise band performed “This I Believe (The Creed).” Rather than an artful expression of worship of an all-powerful, all-encompassing deity, the song is a listing of the basic tenets of Christianity set to the emotionally saccharine soundscapes usually found during the tender moments of a summer romance flick — built by major and minor chords carefully tied to the heartstrings they're intend to pull.

Liberty University praise band performs “This I Believe (The Creed).”

Following the incantation, Nasser returned to the microphone to introduce Liberty University President Jerry Falwell, son of Liberty’s founder, the late Jerry Falwell Sr. — a man infamous for blending political consciousness with evangelical conservatism (among other controversies).

“Nobody loves you more, Liberty students, than our president,” Nasser said of the extant Falwell. “No one cares about you, wants the best for you and wants to see you be world-class leaders more than our president.”

Nasser said that students reciprocate that love, and as an illustration explained that the guttural bellow of “JE-RRYYYY” the students would initiate upon his approach to the podium, was a sign of a support, rather than a cacophonous jeer.

This cheerleading rigamarole, the endless qualifying and over-stressing of statements is identical to the form and feel that I experienced as a student and employee. It always seemed intended to ensure that the perception of Liberty, its students, and its administrators is not left up to chance.

Even Falwell’s gifting of a personalized football jersey to Sanders felt nearly ritualistic; I have witnessed many guest speakers receive memorabilia or honorary degrees over the years and it carried the feeling for me of Liberty trying to “mark” someone for the university’s own edification.

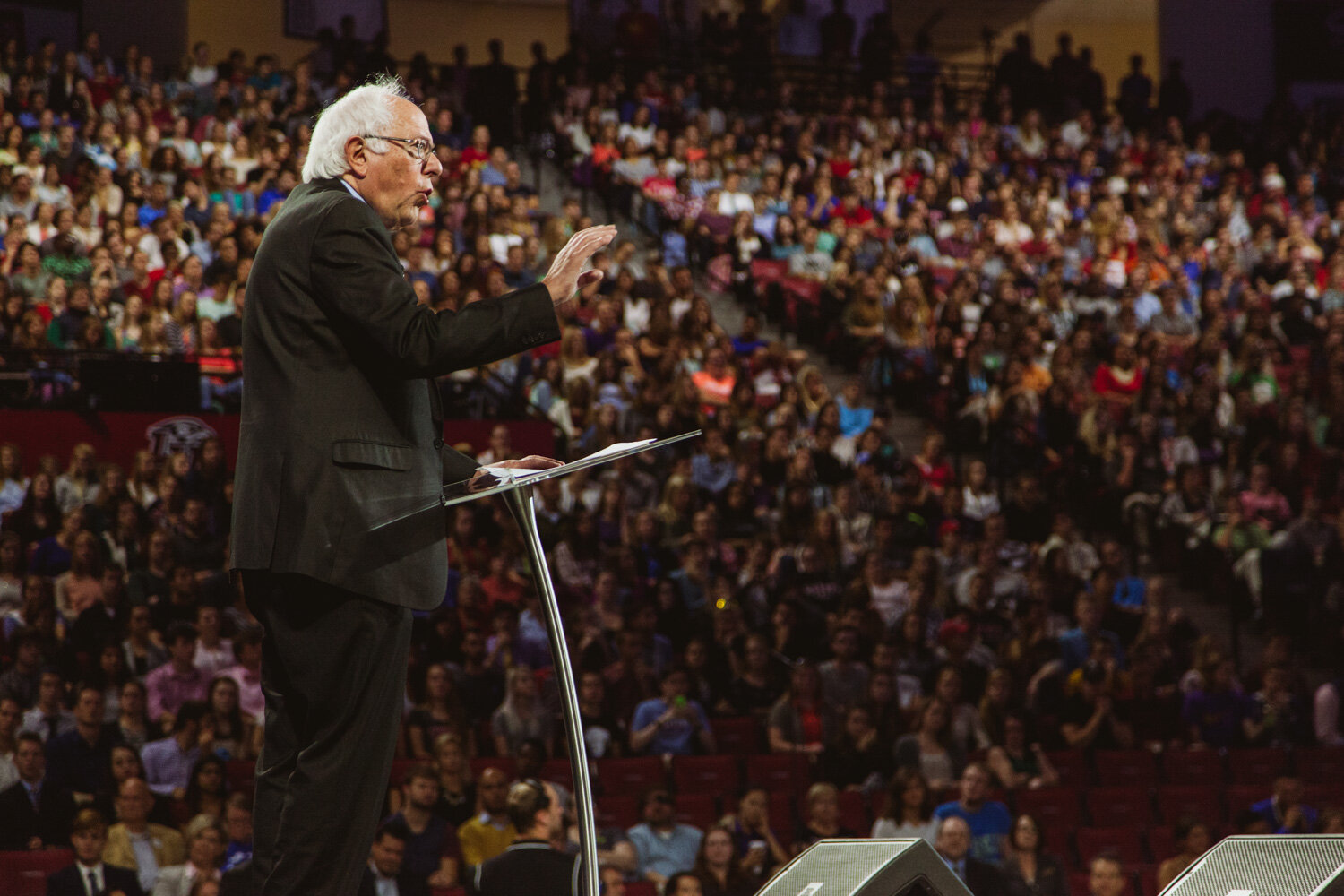

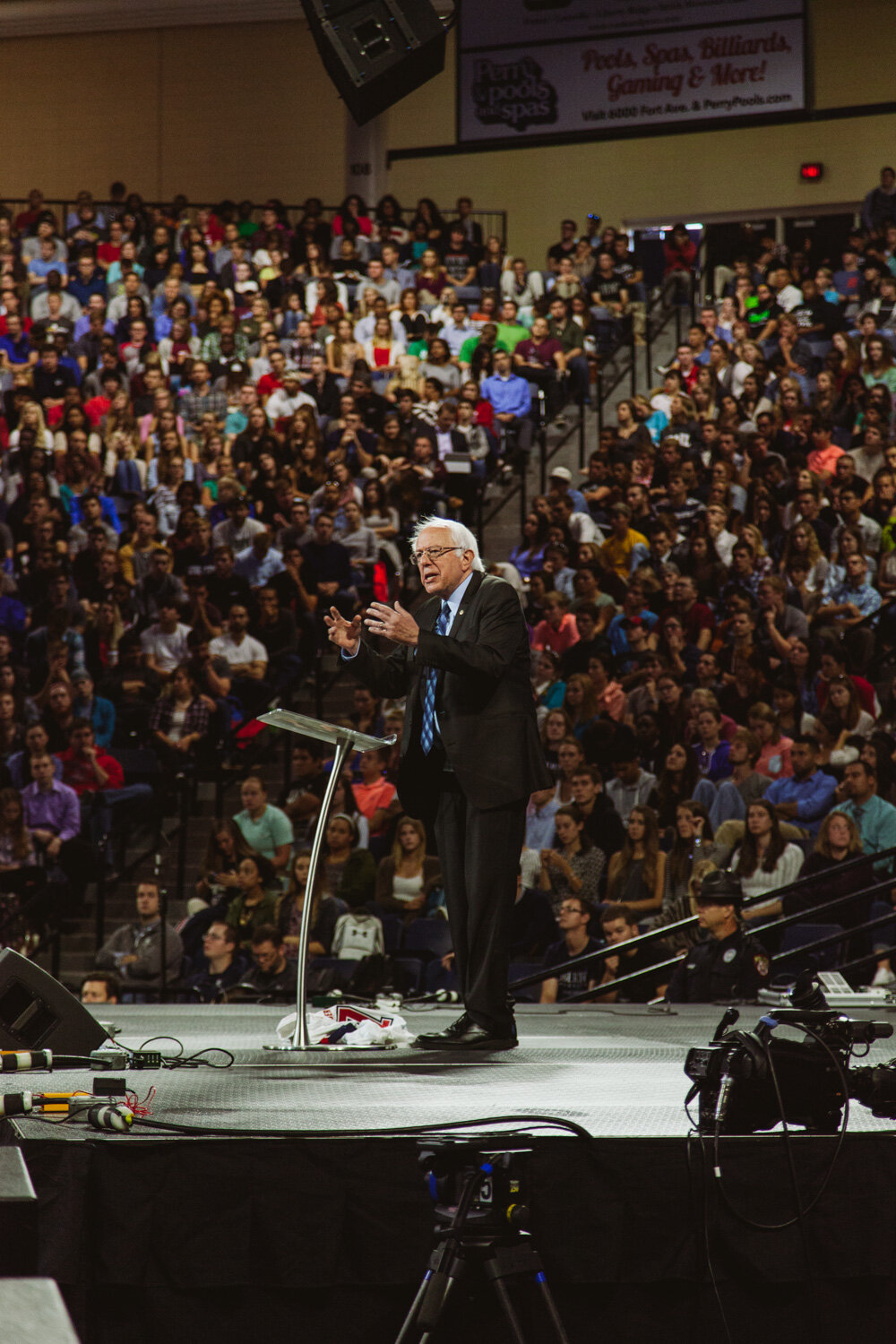

After Liberty had sufficient opportunity to position their cultural niceties and carefully construct their whitewashed house of cards, Sanders began his speech by cutting straight to the quick

“Nobody loves you more, Liberty students, than our president. No one cares about you, wants the best for you and wants to see you be world-class leaders more than our president.”

“[L]et me start off by acknowledging what I think all of you already know. And that is the views that many here at Liberty University have and I [have], on a number of important issues, are very, very different.”

A fair amount cheered in support of those beliefs: gender equality, the right for a woman to control her own body, LGBTQIA+ rights, and gay marriage. Some of the voices belonged to students. As it was during my time as a student, many on campus are not as conservative as the administration’s statements to the press imply.

Liberty University Senior Vice President for Spiritual Development David Nasser addresses the audience. Liberty University President Jerry Falwell Jr. and US Senator Bernie Sanders sit in the background.

“But I came here today,” Sanders said, “because I believe from the bottom of my heart that it is vitally important for those of us who hold different views to be able to engage in a civil discourse.”

In case you missed it, you can watch and read that discourse in entirety here. I won’t analyze or recount much of what he said in this piece, as that has been done in dozens of other places in the days since he came to speak.

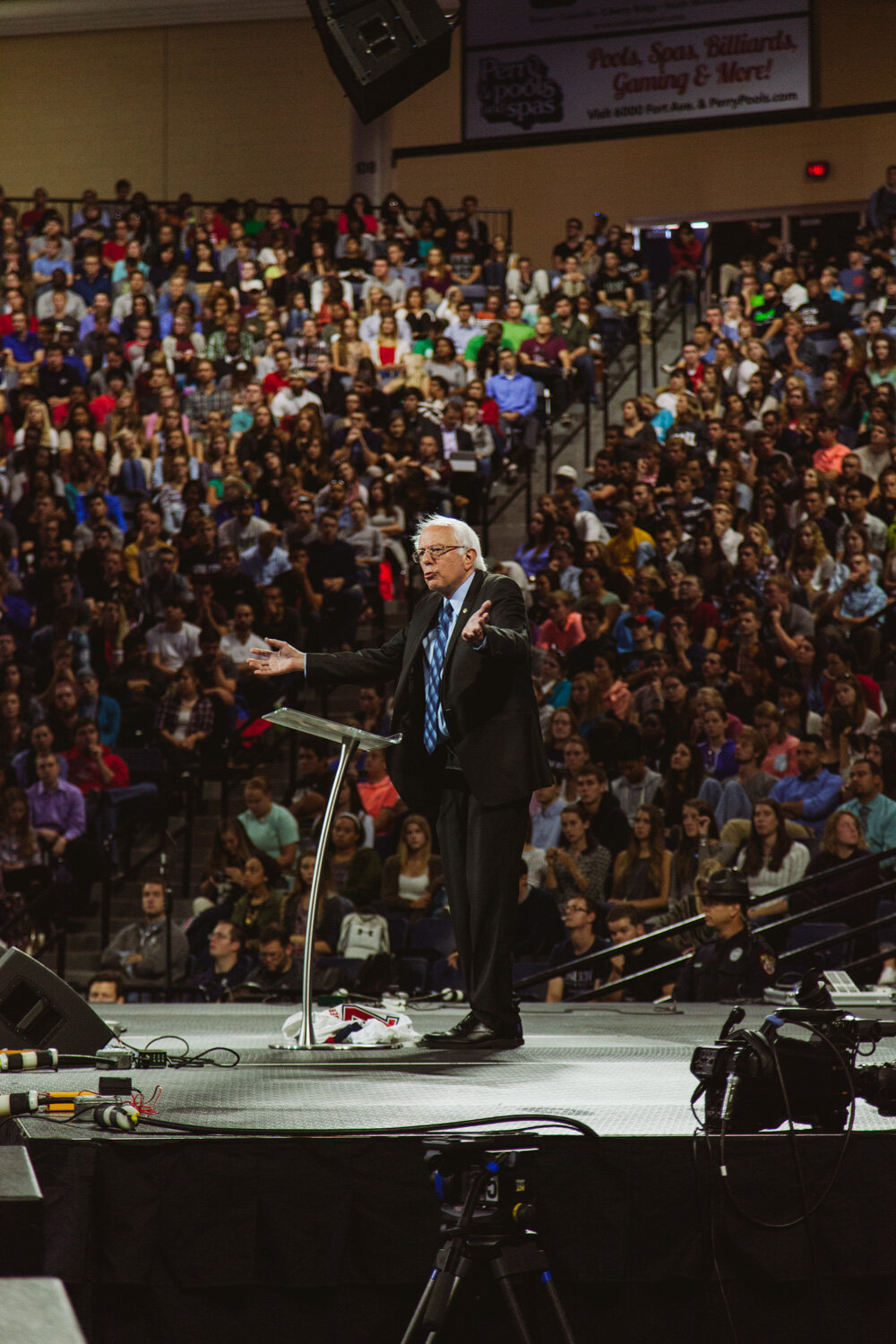

What’s most interesting to me about this event is the interaction between these two forces: Evangelical conservatism and self-spun socialism. A clean Protestant comb-over and the wily white wisps of an irreligious Jew. My past haunts and my present leanings. The fundamentalist and the humanist.

In the evening after the engagement, my co-parent was at a local bookstore preparing for the next day of her teaching job, and I asked her pick me up a copy of Steven Pressfield’s creative manifesto, The War of Art. One section of the book, called “Resistance and Fundamentalism” does an excellent job comparing these forces.

“The artist and the fundamentalist both confront the same issue,” Pressfield writes, “the mystery of their existence as individuals. Each asks the same questions: Who am I? Why am I here? What is the meaning of life?”

So, there is common ground here. Sanders positions that commonality with a different, yet related, question: “What does it mean to live a moral life?” How does one govern morally?

“The difference is that while one looks forward, hoping to create a better world, the other looks backward, seeking to return to a purer world from which he and all have fallen.”

Steven Pressfield

The War of Art

That common ground falls away, however, at the precise moment each party seeks their reply. The fundamentalist, says Pressfield (an authority on ancient Greek civilization, the author of The Legend of Bagger Vance, and a self-described Christian), attempts to find an answer in sacred texts written thousands of years ago, in the context of a society far removed from our own, and attempts to apply those old responses to today’s complex cultural landscape.

“The difference is that while one looks forward, hoping to create a better world, the other looks backward, seeking to return to a purer world from which he and all have fallen,” Pressfield says.

The artist (or humanist — the author uses the two terms interchangeably in this section) seeks to find that answer in the here and now:

“The humanist believes that humankind, as individuals, is called upon to co-create the world with God. This is why he values human life so highly. In his view, things do progress, life does evolve; each individual has value, at least potentially, in advancing the cause.”

The latter approach, is a far greater challenge, but is more in line with the demands of a global society that faces ever-the-more complicated trials and questions.

Reducing the presidential election to two issues (gay marriage and abortion), then, as Christian fundamentalists have stereotypically done, is far more understandable given Pressfield’s distinctions. It’s just so much easier. It requires less thinking and deliberating. There's effort and uncertainty involved.

The fundamentalist doesn’t have to weigh the pros and cons of carrying a fetus to full term when it’s diagnosed with skeletal dysplasia. The fundamentalist doesn’t have to dive into the alleged moral ambiguity of a person who has felt like a stranger in their own body, only to feel whole through modern science’s ability to allow her to affirm the gender she (or he or they) has identified with all along. To the fundamentalist, the answer is clear. The baby will be born (and, in some cases, summarily die). A man is a man and a woman is a woman. Thinking anything outside of that makes you wrong: a murderer, a freak, a pervert, a sinner — lost.

The fundamentalists can sit quietly in their seats, letting their thoughts drift to a homework assignment or their eyes to smartphone screens during the speech and Q&A, while Sanders postures that the United States is not a just nation. But those same individuals can jump into raucous applause when the campus spiritual leader offers a cute rebuttal about inequality: “It’s not a skin issue, but a sin issue.” (Note: A clever turn-of-phrase does not an absolute truth make.)

But there is hope. I spoke with a Liberty University resident assistant who said she cheered for the right for a woman to have control over her own body (although a guy from behind offered her a consequential “fuck you”).

I spoke with a few others who said that you no longer get reprimanded, fined and expelled for being gay at LU, as you would have in the past. And for further sense being made, I encourage you to hear the words of an evangelical pastor (and fellow alumnus) who equated Sander’s plea at Liberty to John the Baptist decrying the Pharisees.

What I’m getting at is that hope is out there, however rarefied. And I think it’s the duty of those who see it to keep that candle burning, if not tip it to the person sitting next to you to light another, and another, letting the wax spill over your hands and Levi’s.

Even though I may seem somewhat positioned against Liberty and its administrative body (arguably with good reason), my frustration really comes from a place where I know people can be better or, rather, must be better if we are going to keep this beautiful thing called human life spinning for another few thousand years or so.

My preference is to not be ashamed of the fact that my undergraduate degree is from Liberty University, a place not exactly synonymous with intellectual integrity and compassion for those who are different.

My preference, as it was on that day, is for positive change to take me by surprise.

At Liberty, the cultural climate seems to have improved from the time my supervisors tasked me with editing less-than-favorable information from the school’s Wikipedia page (I declined), but there’s a long way yet to go. I hope to be able, as I was on that day, to take an electric blue and pink polka dot bicycle ride across town (like a one-person queer pride parade) to witness it happening.

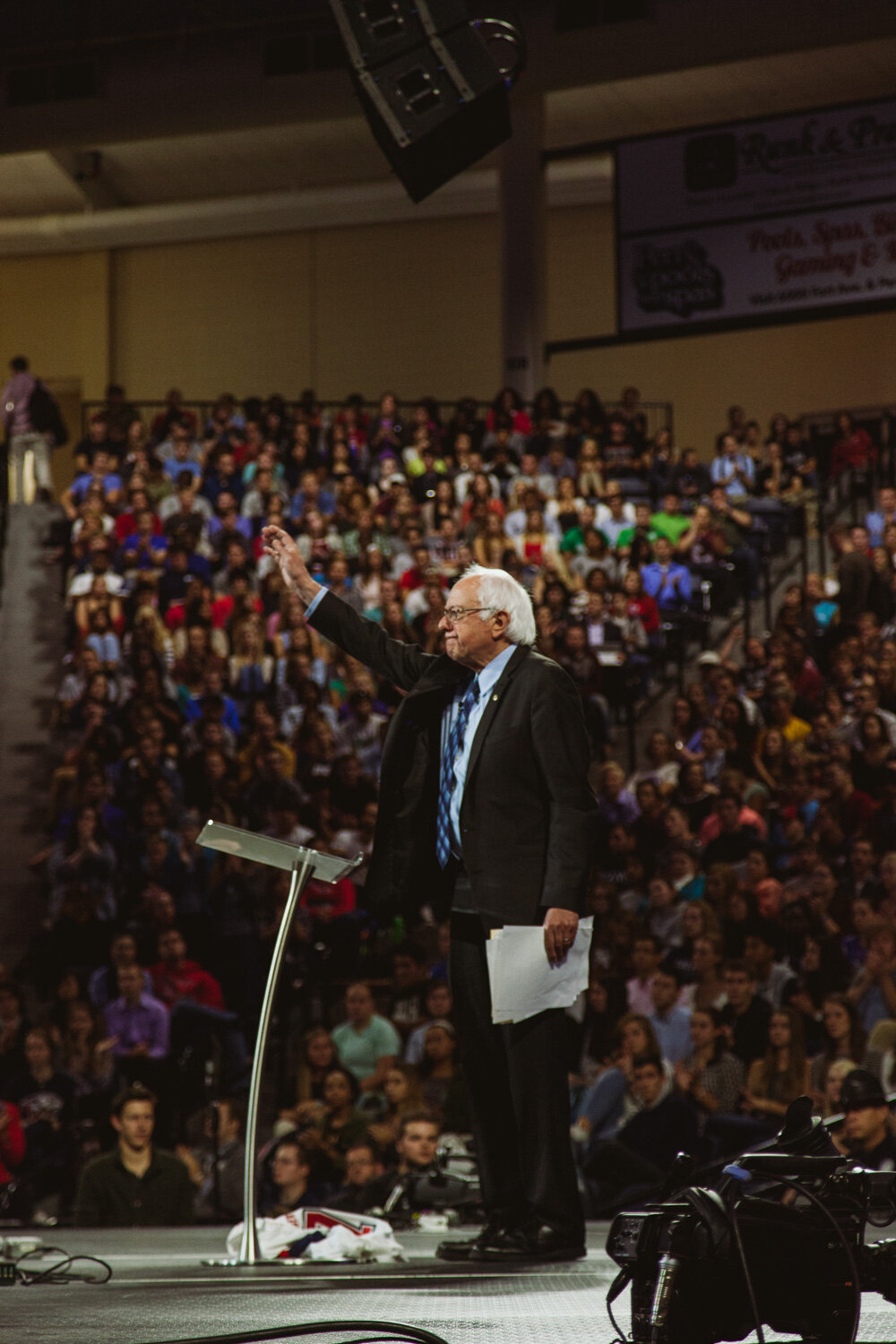

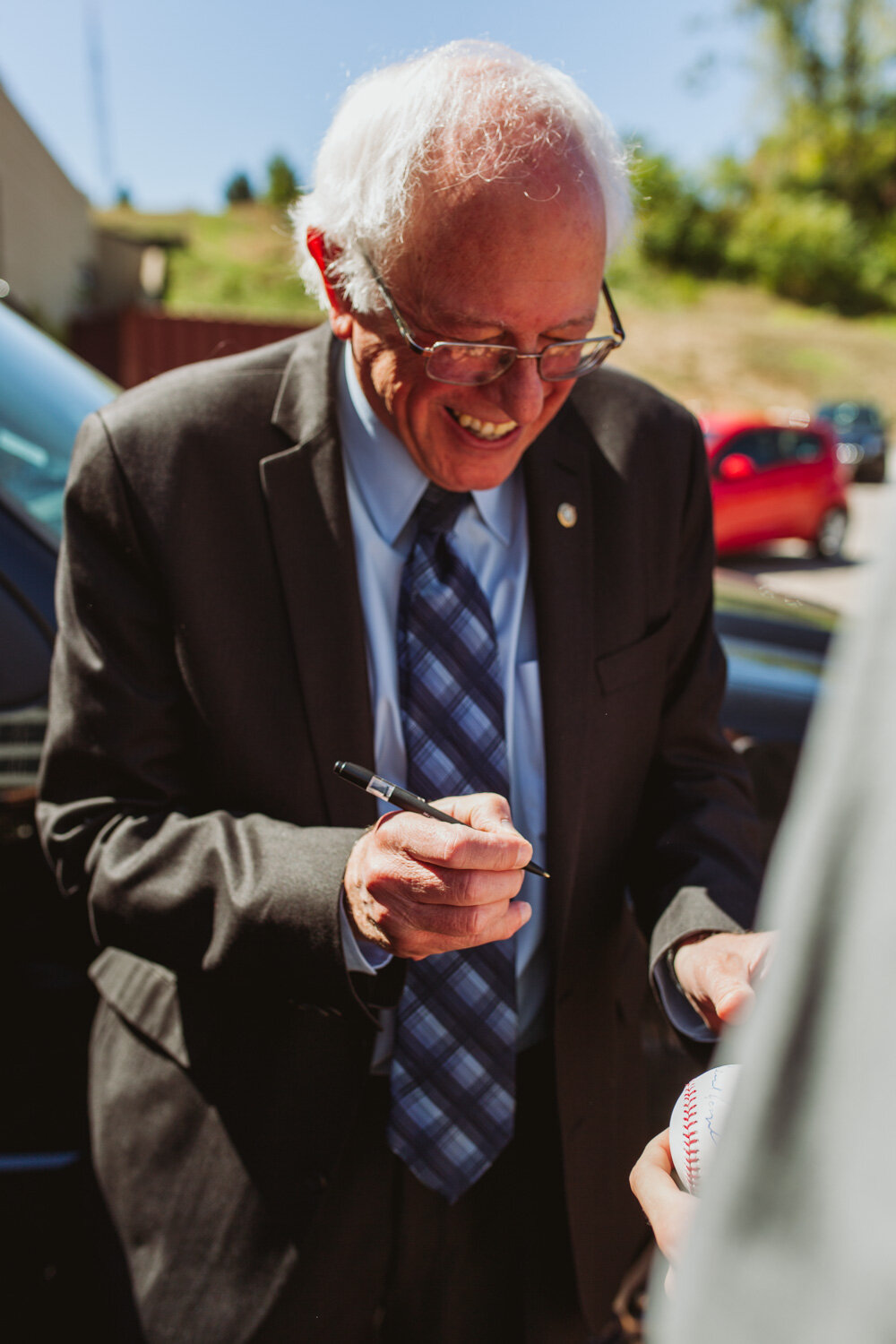

Once the service was over, I ran into a couple of friends who are currently enrolled. Their energy at hearing Sanders speak was electric, encouraged and invigorated. They told me to follow them around back of the building so we could possibly meet him.

And so I did.

He graciously exited the SUV when he saw us, and said he had enough time to take a few photos. When it came my turn to say hi, I handed my DSLR to a friend and told him how to shoot (but neglected to give instructions on the focus, as you can see below).

I had never met a U.S. senator before, much less a presidential hopeful, and so I was grateful for the opportunity and wanted to say something meaningful. What I wanted to tell him was that in my 12 years of voter eligibility, I’d always cast my ballot in favor for who seemed like the lesser of the two evils. This election could be different. There’s a candidate who I believe actually represents me and the America I was raised to believe could be possible.

OOPS: Forgot to tell my friend how to focus my DSLR for this shot of US Senator Bernie Sanders and myself.

But I couldn’t get any of that out. Instead, I shook his hand, smiled for the camera and said, “Thanks for not being full of shit.”

He laughed, and looked into the camera. I’m pretty sure he knew what I meant.

Thoughts? Questions? Frustrations? Let’s talk about it (below).

My name is Marcelo Asher Quarantotto.

I WRITE WITH WORDS, PHOTOS, VIDEOS, WEBSITES AND MUSIC.I am a father of three beautiful daughters and husband to the most gracious, saintly creature I've ever met. (You'll find pictures of them here from time to time.) I am also a multidisciplinary storyteller.